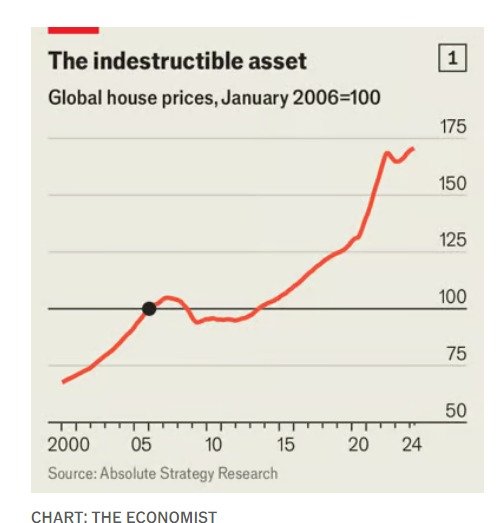

Is a fresh housing boom under way? In April a house-price index for the world, excluding China, rose by more than 3% year on year (see chart 1). American house prices are 6.5% higher than a year ago, Australian ones are up by 5% and Portuguese ones are soaring. In other countries, the market looks surprisingly strong given years of high interest rates (see chart 2).

These figures follow a tough period. Adjusted for inflation, prices have fallen by 20% in Canada, Germany and New Zealand. They are well off their peaks in some American cities, including San Francisco and Phoenix. In Boise, Idaho, where prices soared during the covid-19 pandemic as people sought living space, values are down by over a tenth. Meanwhile, higher interest rates, and mortgage costs, have made people worried about their spending on housing: the share of Britons who say they find it “very” or “somewhat” difficult to make rent or home-loan payments has risen from 24% in early 2022 to 41%.

Yet it is surprising that things have not been more difficult still. Since a trough in 2021 the rate on a typical 30-year mortgage in America has risen by about four percentage points. Rules of thumb derived from the academic literature indicated that nominal house prices would fall by 30-50%. In fact, they have hardly fallen at all in nominal terms. In real terms (ie, adjusted for inflation) global house prices are down by 6% from their peak—but that puts them in line with their pre-pandemic trend. The downturn also claims the crown as the shortest ever, lasting just a few months.

Some worry that high rates will eventually cause a proper crash. Rohin Dhar, a housing expert, has pointed out that lots of listings in Florida feature the phrase “motivated”, which implies people are selling in a hurry. But in America as a whole, the share of mortgages in delinquency has never been so low, at 1.7%, compared with more than 11% at the height of the global financial crisis of 2007-09. Elsewhere the situation appears to be similarly benign. In New Zealand, the rich country that was hit hardest by the housing downturn, arrears are in line with the pre-covid norm. With the exception of Germany, there is less distress in the euro zone, too.

American observers typically credit the country’s mortgage system, which relies heavily on long-term fixed rates, for its resilient housing market. Other countries have recently moved in an American direction. Fixed-rate mortgages protect homeowners from higher rates, meaning fewer firesales that can drag down house prices. They also give homeowners a strong incentive not to move house, because they would need to get a new mortgage at a higher rate.

But fixed-rate mortgages are not the only explanation for housing-market resilience and recent price growth. After all, applications for new mortgages remain reasonably strong across much of the world, even if they have fallen from pandemic highs. And the National Association of Realtors, an American lobby group, finds surprisingly little evidence that higher rates are dissuading people from buying a first house or moving into a new one. According to its recent research, only 8% of people said that “getting a mortgage” was one of the “most difficult steps” of the home-buying process, marginally up from 7% in 2021.

Three further factors could explain why global house prices are once again rising: immigration, sacrifices by mortgage-holders and the strength of the economy. Take immigration first. The rich world’s foreign-born population is rising by about 4% year on year, its fastest on record. Official figures on which such calculations are based probably understate the scale of the shift, since illegal immigration has also surged, especially in America. This, in turn, is pushing up both house prices and rents, argues Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics, a consultancy, since the new arrivals need somewhere to live. Estimates by Goldman Sachs, a bank, imply that Australia’s current annualised net migration rate of 500,000 people will raise house prices by around 5%.

The second factor concerns sacrifices. People across the rich world are dealing with higher mortgage costs by cutting back on other sorts of expenditures. A recent survey by YouGov, a pollster, found that one in five variable-rate-mortgage holders in Britain say they are making “large” cuts in household spending, even as those on fixed-rate deals are less perturbed. Others are reaching behind the sofa. A recent report by the Norwegian central bank noted that many households “have drawn on accumulated savings” to service debt.

Longer mortgages are helping many to spread out repayments, sacrificing wellbeing in the future to reduce mortgage payments today. The Canadian government recently announced it would extend the payback period on some state-backed loans from 25 to 30 years. According to Centrix, a credit-reporting agency, 6.4% of New Zealand mortgages originated last year will last for more than three decades, compared with 2.3% in 2020. The Bank of England recently noted that in Britain “the trend towards longer-term mortgages had continued” such that for 40% of new mortgages “borrowers would be past the current state pension age at the end of their mortgage term”.

The most important factor relates to the economy. True, households are paying out more in interest, but there is also more coming in. Some benefit from higher interest income on their savings, which in the eu has risen by nearly ten times as much as interest payments have since 2020. Unlike in the housing crash of 2007-09, the labour market is also helping (and the banks have not imploded). Since 2021 average wages across the rich world have gone up by about 15%, while unemployment remains close to an all-time low. In every country for which we can find data, the increase in households’ labour income in recent years dwarfs increases in interest costs. No one likes higher mortgage payments, but the vast majority of people can afford them.

Do not be surprised, therefore, if house prices continue to rise. Some central banks have already started to cut interest rates as inflation declines; America’s Federal Reserve will follow before the year is out. Across the rich world, wage growth remains in good shape. Falling inflation will give mortgage-holders breathing room. And any increase in demand for housing will run up against constrained supply. Unless something drastic changes, the world’s biggest asset class is about to get bigger still.

Comments are closed.