Where the heck are we? Many economists are asking themselves this question. Investors should, too.

The economy normally follows a well-worn pattern known as the business cycle. The cycle starts turning with a burst of vigorous expansion. Then comes a long patch of more moderate growth. Eventually a slowdown occurs, which leads to a recession that clears out the excesses of the past cycle. This sets the stage for a new expansion to kick the cycle into gear all over again.

iStock-1200508619.jpg

The first job of every smart investor is to know where in the cycle we are. But, right now, that is difficult, because things are moving so fast.

Over the past half century, a typical business cycle took eight to 10 years to come full circle. The current cycle is progressing more rapidly, like the time-lapse video of a baby growing into a middle-aged man, all in the space of a couple of minutes.

Less than two years ago, the world was in the depths of a record-busting recession. A few months later, we were in a full-on expansion, with stock markets hitting record highs and unemployment plunging.

And now? We seem to be entering into the more restrained growth of a mid-cycle economy. But we may not tarry here as long as usual.

After this week’s announcement that U.S. inflation hit a 40-year high of 7.5 per cent in January, big interest-rate hikes are looming as the Federal Reserve, the Bank of Canada and other central banks strive to bring runaway prices under control. If a series of aggressive rate hikes start to turn the screws on economic growth, the early stages of a slowdown could be closer than most people think.

“This could ultimately be a mere five-year cycle rather than the 10-year cycles that preceded it,” Eric Lascelles, chief economist at RBC Global Asset Management, noted this week.

The challenge is how to navigate such a foreshortened cycle. If you’re of a cautious nature, you may be tempted to start tilting toward defensive stocks, such as utilities and consumer staples, or even begin edging into bonds.

Many investment strategists, though, are leaning in the opposite direction. At BNP Paribas, for instance, Maya Bhandari and Daniel Morris argue that the five to six hikes they are expecting this year from the Fed won’t substantially derail the stock market or global growth. In a note on Friday, they continued to recommend holding a higher than usual proportion of stocks in your portfolio.

If all this sounds like a gigantic guessing game to you, join the club. This cycle’s inscrutability stems from the unprecedented depths of the pandemic recession, the unprecedented amounts of stimulus that governments delivered in response, and – not least – the unprecedented challenges that all this unprecedentedness has created for data watchers.

Case in point: the U.S. jobs report for January.

The report, published Feb. 4, took economists by surprise because they had braced themselves for downbeat numbers that would reflect hundreds of thousands of jobs lost as a result of the Omicron variant. Instead, the report showed the economy had created nearly half a million jobs.

This stunning and very upbeat result seemed to indicate that the world’s biggest economy was still early in the business cycle. But wait. Over the past week, as economists scoured the report, a different picture emerged.

It now seems that the huge reported gain in jobs may be largely a result of how government statisticians modified their techniques for adjusting raw numbers to account for seasonal fluctuations in the economy. This means adjusting not just for recurring events, such as Christmas hiring sprees, but also for the impact of one-time events such as COVID-19 that (hopefully) won’t recur but aren’t exactly temporary either.

Adjustments are tricky stuff and it now appears the reported numbers could be a statistical mirage. Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics, told The New York Times that using the government’s previous adjustment methodology the U.S. economy actually lost 300,000 jobs in January.

So go figure. The pandemic has shaken economies in unexpected ways, throwing up clouds of hard-to-read data. What stage of the cycle are we in? It all depends on which indicators you trust.

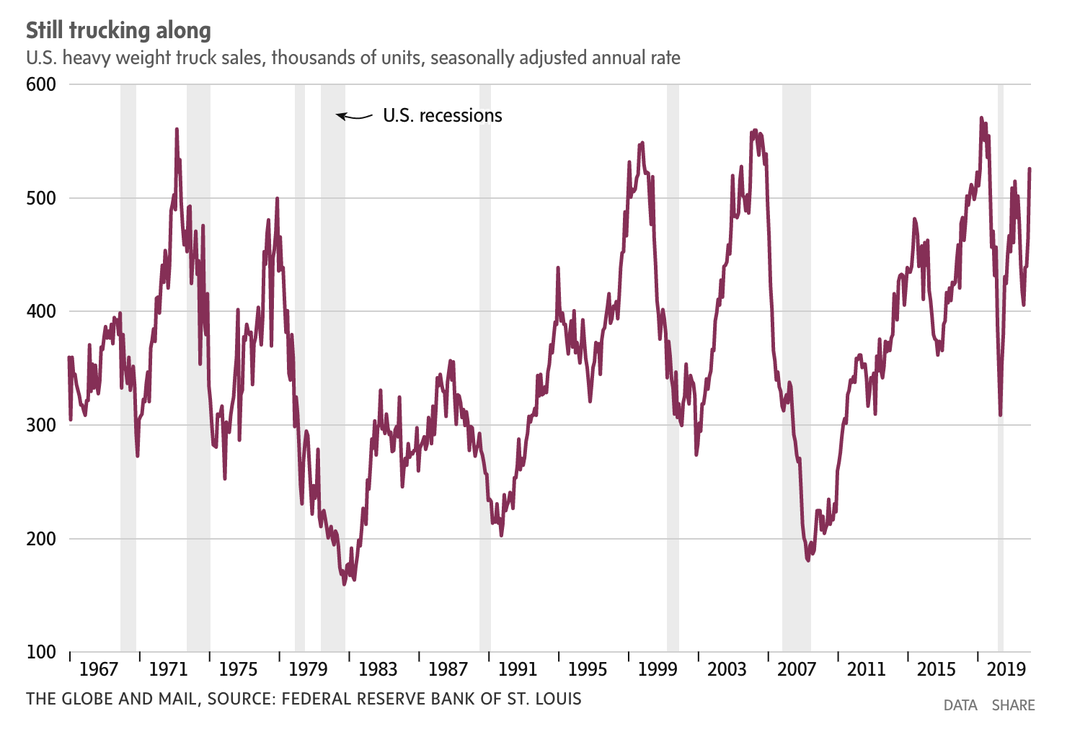

At times like this, it helps to look at a wide range of gauges than usual. Consider U.S. sales of heavy trucks, for instance. (You can find them at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’s data site at fred.stlouisfed.org)

The logic here is simple: No one buys big trucks for laughs. They are purchased by businesses because they see good times ahead. So long as heavy truck sales are on the upswing – as they are now – the North American economy is probably in decent shape.

Another gauge to follow is the share price of the U.S. Global Jets ETF (JETS), an exchange-traded fund that holds shares of airlines and aircraft manufacturers around the world. It is a useful indicator of how far the aviation industry – and the global economy in general – has rebounded from the pandemic. Right now, its lacklustre but relatively steady share price suggests most people don’t see any quick end to the pandemic era but aren’t panicking either.

The combined message from trucks and jets is that we are still firmly in the middle of this business cycle. That is good news for most investors. But given how fast things are changing, they should check back regularly.

Comments are closed.