Inflation in Canada plunged unexpectedly in January, and economists say it could push the Bank of Canada to cut interest rates sooner than previously thought.

iStock-1491593096

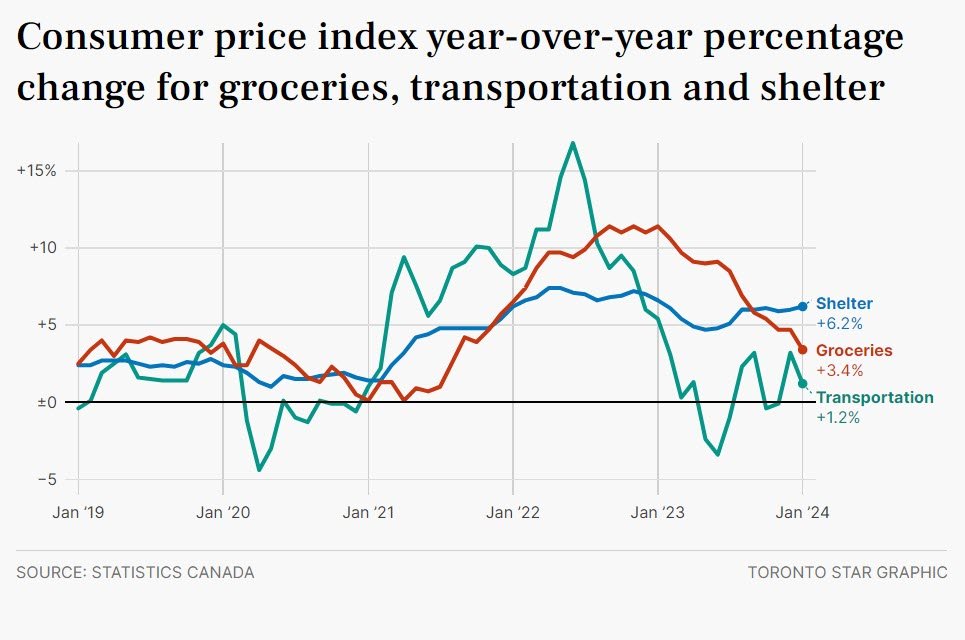

The Consumer Price Index — a broad-based measure of inflation — was 2.9 per cent higher in January than it was a year ago, Statistics Canada reported Tuesday. A consensus of economists surveyed by Bloomberg had expected the data to show that the annual rate of inflation was 3.3 per cent in January. Inflation was 3.4 per cent in December.

“There is little debate on this one — it’s a much milder reading than expected,” said BMO chief economist Douglas Porter in a research note after the data was released.

It’s the first time in seven months that ‘headline’ inflation has dipped below three per cent. Mortgage interest costs were the fastest-rising element of CPI, rising 27.4 per cent from a year ago. Excluding mortgage costs, CPI rose by two per cent — the Bank of Canada’s target rate for headline inflation.

The fall was so deep, and so widespread, said Porter, that it could push the Bank of Canada to cut interest rates in the next few months.

“Clearly today’s result makes rate cuts much more plausible in coming months, and we remain comfortable with our call that the Bank will begin trimming in June,” said Porter.

Before the January inflation numbers were released, trading on the overnight interest swap market had the odds of a June rate cut by the Bank of Canada at roughly 50 per cent. Shortly after the release, that jumped to just under 70 per cent, Porter noted.

Speaking to reporters on Parliament Hill, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called the inflation number “a bit of good news,” and noted that the January rate falls within the Bank’s official target range of one-to-three per cent inflation.

“We are optimistic that the Bank of Canada will start bringing down interest rates sometime this year, hopefully sooner rather than later,” Trudeau said “but that is their decision to make.”

Bank governor Tiff Macklem has said repeatedly that the bank doesn’t intend to cut interest rates until inflation is “sustainably” heading to two per cent, the middle of its official range.

The market is now pricing in a 55 per cent chance of a cut as soon as April, up from 33 per cent before the data was released. There’s also a small chance that the Bank could announce a cut March 6.

The Bank of Canada has raised its key overnight lending rate 10 times since March 2022 as it attempts to bring inflation under control. The overnight rate is now at five per cent, up from 0.25 per cent when the rate hikes began.

The theory is that by making it more expensive to borrow money, consumers and businesses will spend less, driving down prices and slowing the economy.

While inflation has come down substantially from its peak of 8.1 per cent in June 2022, it’s still higher than the bank’s target of two per cent.

Pedro Antunes, chief economist at the Conference Board of Canada, said the January report is welcome relief, especially in comparison to higher than expected inflation numbers south of the border released last week.

“This is great news. I was concerned, especially after what we saw in the U.S. last week,” said Antunes. The annual rate of inflation in the U.S. was 3.1 per cent in January, while most analysts had been expecting 2.9 per cent.

Antunes and his colleagues at the Conference Board are still expecting the Bank of Canada to start cutting rates “mid-year,” and suggested that a single month’s reading won’t change the Bank’s timelines all that much.

“I think unless the economy really takes a real dive, they’re not going to change their timing,” Antunes said.

David Macdonald, an economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, agreed that the Bank of Canada probably won’t change its timelines much, if at all, because of the January inflation number. But the rate-cutting should have already begun, he said.

“I don’t think this radically changes the picture,” said Macdonald. “I think they should have started cutting months ago.”

The Bank’s rate hikes, argued Macdonald, are now making inflation worse, either directly — through mortgage rate increases — or indirectly, through landlords increasing rents to help cover their own rising costs.

“We’re at a point now where shelter is the biggest single driver of inflation,” said Macdonald.

Comments are closed.