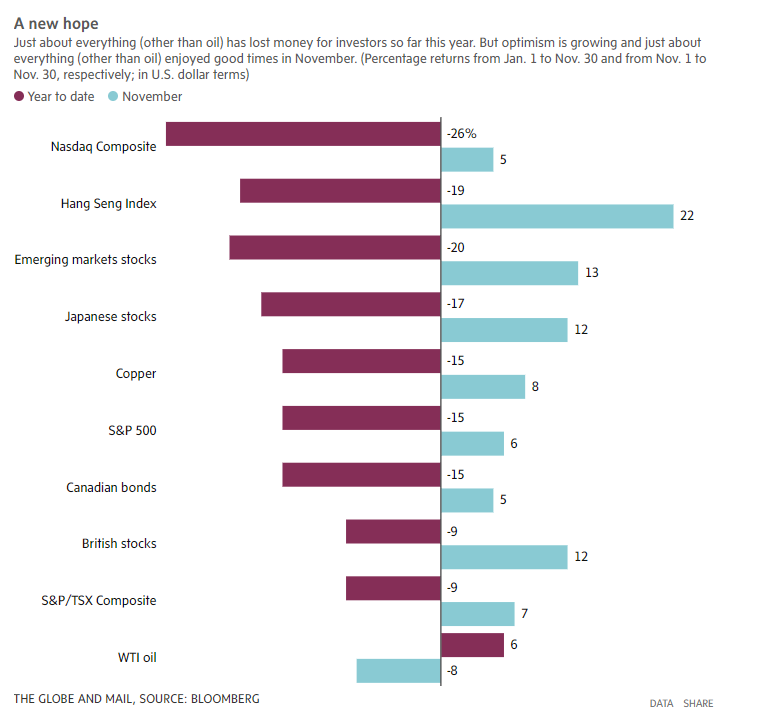

Investors have a new spring in their step. After months of losing money on just about everything they owned, they suddenly made money on almost anything they touched in November.

The turnaround was remarkable. Consider the Hang Seng Index of large stocks in Hong Kong. It had lost more than a quarter of its value over the first three quarters of the year. In November, it jumped 22 per cent higher (in U.S. dollar terms).

iStock-511239833.jpg

Similarly, the S&P/TSX Composite in Canada and the S&P 500 in the United States powered upward in November after months of stinging losses. So did British stocks, Japanese stocks, emerging markets stocks, Canadian bonds and copper.

What’s driving this suddenly upbeat mood? Jim Reid, a research strategist at Deutsche Bank, identifies two major factors. First is a conviction that the world is over the worst when it comes to inflation. Second is the widespread belief that China is going to have to ditch its zero-COVID strategy and reopen its economy after a couple of years of rotating lockdowns.

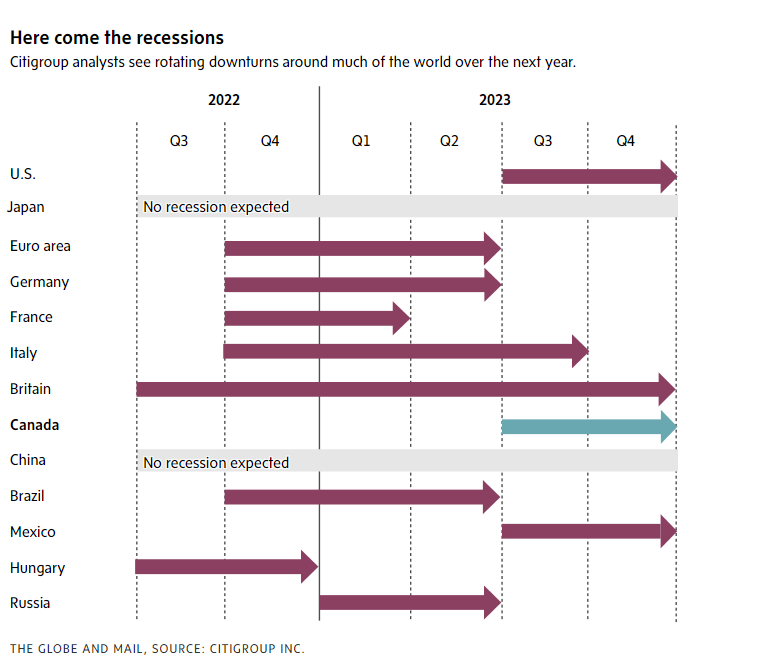

A couple of other assumptions also seem important. One is the idea that, yes, recessions are likely in many countries, but that those downturns will be brief and mild. Finally, there is the notion that oil and other energy prices are no longer in danger of running out of control.

All four ideas seem reasonable enough when examined one by one. What’s not so clear is how easily they fit together when taken as a whole.

Take inflation and recessions, for example. They are two sides of the same coin. A slowing economy should reduce demand and thereby relieve pressure on inflation. The question is just how big a downturn will be needed to bring prices back under control.

Investors appear to be assuming only mild recessions will be required to chop inflation from its current level around 7 per cent in Canada and the U.S. and bring it down to the 2-per-cent target set by policy makers. This seems rather hopeful.

Deutsche Bank recently examined the experience in several major industrial countries, including Canada, since the 1960s. It found that any time the trend in inflation declined by two percentage points or more, that decline was accompanied by a rise in unemployment of at least two percentage points – which sounds more like a moderately severe recession than a mild one.

The economics team at investment manager BlackRock Inc. is even grimmer. Taming inflation in the U.S. is likely to require a deep recession, they argue in a recent outlook. If the Federal Reserve is truly intent on grinding inflation all the way back to 2 per cent, it has no choice but to deal “a significant blow to the economy,” they say.

To sum up: We may get radically lower inflation in 2023 and we may get only mild recessions, but we are unlikely to get both together if past patterns prevail.

It isn’t clear how this tension will be resolved. Maybe the economy is truly in a new place and inflation will fade away of its own accord. Or maybe central banks will ease up once inflation falls below, say, 4 per cent. Or maybe policy makers will accept no compromises and endure a painful recession to hit their 2-per-cent inflation target.

Investors may want to bear this uncertainty in mind.

They should also ask themselves if the current optimism about China’s reopening economy really fits with a benign outlook for global inflation and global oil prices over the next few months.

If China were to suddenly reverse its zero-COVID strategy and open up its economy, allowing more street traffic and more free movement of people, its demand for oil would spike. So would its demand for other goods.

This could prove to be a headwind for global asset prices because it would intensify inflationary pressures and prod central banks to keep interest rates at lofty levels, according to Thomas Mathews, senior markets economist at Capital Economics.

The good news – if you can call it that – is that Beijing is likely to move only slowly on reopening China’s economy, Mr. Mathews writes in a note. He argues the most likely scenario is for the reopening to take place some time toward the end of 2023.

If investors can glean anything from this mountain of what-ifs, it’s that markets are unlikely to follow a straight line up or down over the next year.

Deutsche Bank, for instance, sees the current rally continuing over the next few months, driving the S&P 500 to a high of around 4,500 from its current level around 4,050. The bank then sees stocks plunging by roughly a quarter as recession bites, pulling the index down to 3,250 in the third quarter. Policy makers should finally relent at that point and start chopping rates. This should allow the index to recover to 4,500 by year-end 2023, Deutsche Bank says.

Maybe so. But a simpler way to express much the same idea is to say that uncertainty is unusually high right now. The recent rally provides investors with a fine opportunity to sell anything they’re not comfortable holding for the long term. They may want to take the opportunity to buckle up for what could be another year of volatility.

Comments are closed.