Football fans can hardly accuse Qatar of being tight-fisted. The Arab state has reportedly spent $300bn in the 12 years since it won the rights to host the men’s World Cup. It only expects the tournament to inject $17bn back into its economy. Much of that spending spree has gone into building infrastructure, including a whizzy new metro system built to accommodate the 1.5m visitors expected to show up to football’s biggest party. Organisers insist all the construction will serve a purpose even after the final goals are scored. They should hope so. As an investment, sporting mega-events are almost always a dud (see chart).

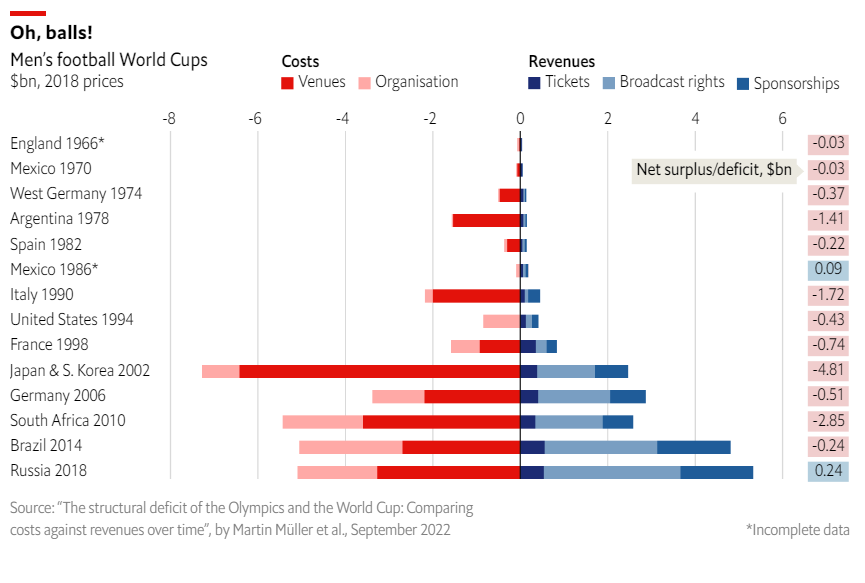

Between 1964 and 2018, 31 out of 36 big events (such as World Cups or summer and winter Olympics) racked up chunky losses, according to researchers at the University of Lausanne. Of the 14 World Cups they analysed, only one has ever been profitable: Russia’s in 2018 generated a surplus of $235m, buoyed by a huge deal for broadcasting rights. Still, the tournament only managed a 4.6% return on investment. (The data for Mexico’s World Cup in 1986 is incomplete. It probably ran a deficit.)

Almost all the main expenses fall on the host country. FIFA, the sport’s governing body, covers only operational costs. Yet it takes home most of the revenue: ticket sales, sponsorships and broadcasting rights go into its coffers. The last World Cup, for instance, scored FIFA a cool $5.4bn, part of which is then transferred to national teams.

The Lausanne data only includes expenses related to venues, such as constructing a stadium, and logistics, such as staffing costs. It ignores the value of indirect projects, like Qatar’s metro infrastructure and new hotels. Some infrastructure projects make economies more productive in the long term. But many costly stadiums eventually go unused, and the events rarely spark economic development in surrounding areas.

Residents of host cities have begun questioning the benefits of their governments spending billions of dollars on large sporting events. As a result, fewer countries are volunteering as hosts. Seven cities bid to host the summer Olympic Games in 2016; for 2024 there were only two eventual bidders.

These huge costs are new to the sporting world. The World Cup in 1966, featuring 16 teams, cost around $200,000 per footballer (in 2018 prices). In 2018, that figure jumped to $7m. Costs have been driven by building more new stadiums for every tournament. In Qatar, seven of the eight stadiums have been built from scratch; in 1966 England did not build any.

Economics aside, Qatar is also struggling to bank the prestige that host cities aim to attract. According to one analysis, two-thirds of coverage in the lead up to the World Cup in British media has been critical, focusing on the desert state’s poor human-rights record. Fans may also be unimpressed by its abrupt ban on alcohol in stadiums. As with any party, hosting is not all it’s cracked up to be. ■

Comments are closed.