On November 2nd the Federal Reserve raised interest rates by three-quarters of a point, bringing its benchmark rate to a range of 3.75-4.0%. The central bank reiterated its commitment to returning annual inflation—which is above 8% on the headline measure, and exceeds 6% on the index tracked by the Fed—to its 2% target. Getting there could require a painful recession. Yet although the Fed must treat the 2% target as sacred, it has surprisingly flimsy foundations—and could yet be changed.

A goal of 2% was first adopted in New Zealand in the early 1990s. Having decided to target inflation, policymakers had to pick some number. Gradually, the framework was aped by central banks around the world. The Fed has been formally shooting for 2% since 2012. Some economists argue that the target should be higher. As inflation rises so, over time, do interest rates. A higher starting point for interest rates would have been handy going into the global financial crisis of 2007-09, after which they plummeted to almost zero, all but exhausting central bankers’ ability to boost growth with monetary stimulus.

Nobody thinks inflation should stay above 8%. But some economists argue that today’s surging prices at least provide the opportunity to switch to a modestly higher goal of 3% or 4%, reducing the risk of interest rates once again falling to near zero in a future crisis. (A change would also allow central bankers to go a little easier on their economies today.) It is surprisingly hard to muster an argument against reform that is rooted in the economic costs of inflation, which are hard to pin down. Abstract logic, such as the idea that inflation distorts the relative prices of goods, tends to produce underwhelming results when economists take the theory to the data.

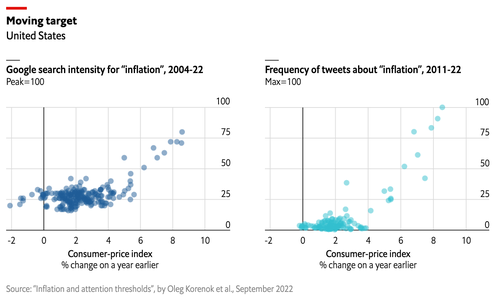

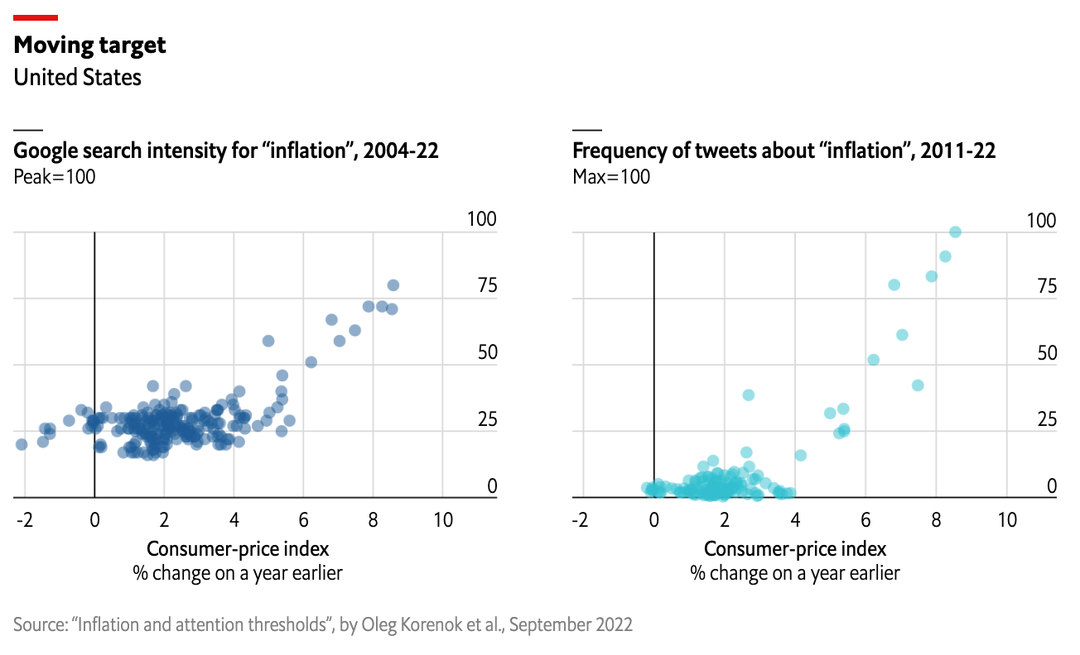

An alternative idea is that the downside of inflation is mainly psychological: the public hates it. But how fast can prices rise before it troubles them? A working paper by economists at Middlebury College and Virginia Commonwealth University attempts to answer this question by estimating the point at which households and businesses start paying attention to inflation. Using data on Google searches and tweets about “inflation” in 37 countries between 2004 and May 2022, the authors find that, when inflation is low, such searches tend to be uncorrelated with actual inflation, whereas at higher inflation rates, they tend to move in sync (see chart). The threshold varies from country to country. In America it is 3.6%; in Germany it is 2.6%; in Britain just 2.2%.

That suggests there may be some scope for America to raise its inflation target. Price rises of 3% might be low enough for the public to relax, but high enough to satisfy reformers. Critics say that the promise of 2%, once made, should be inviolable. As the costs of disinflation mount, though, central bankers may find themselves weighing probity against pragmatism. ■

Comments are closed.