The cost of a comfortable middle-class retirement is less than a lot of people think.

Still, fitting your desired retirement lifestyle into what you can afford isn’t necessarily easy.

It’s often a bigger challenge for singles, because they can’t share costs for things like accommodation and cars the way couples usually can.

If you’re in that situation, focus on making the most of whatever retirement spending budget you can afford. You should carefully match your desired retirement lifestyle to your spending, set spending priorities to get what’s most important, be creative and stay flexible, advises Janet Gray, an advice-only certified financial planner with Money Coaches Canada.

iStock-979251076

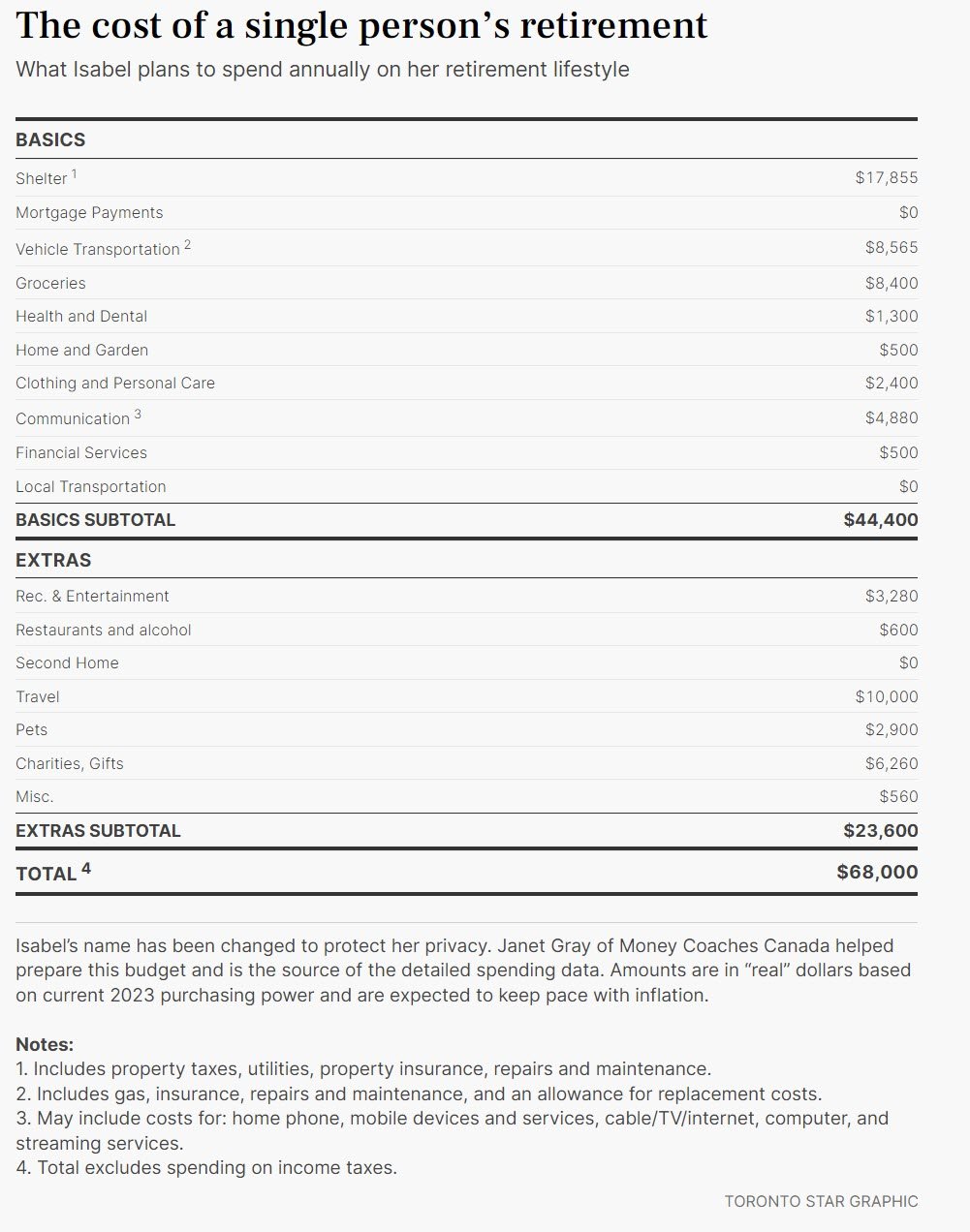

To provide an example, we present the planned retirement budget of Isabel, a single mother in her mid-50s who lives in a mid-sized Ontario city and plans to retire in about five years. (Her name has been changed to protect her privacy. Her budget details were provided by Gray.)

Isabel plans to spend $68,000 a year to realize her desired retirement lifestyle. If you’re on a tighter budget, you should be able to still enjoy a comfortable retirement on $50,000 or $60,000, but you will need to prioritize spending carefully. (Those amounts are in today’s dollars and don’t include spending on income taxes, which we’ll discuss in a minute.)

Retirement spending is one key factor among several in determining the amount of savings you’ll need to start retirement. In my next column, I will show how to fit these factors together.

Isabel’s plans

Isabel is a government employee with two kids who live at home while attending university. She expects them to be financially self-sufficient by the time she retires. She owns her home and has no debts.

Her spending plans include $44,400 a year for basics like accommodation, groceries and transportation, as well as $23,600 for “extras” like travel, dining out and gifts to her kids.

“She does want to travel,” says Gray, citing Isabel’s $10,000 travel budget. Other interests have more modest costs: “She wants to enjoy her house, she enjoys gardening, things like that.”

Isabel plans to spend an unusually large amount on gifts, with plans to set aside just over $6,000 a year. This is mainly to help her two children with things like weddings and home down payments. “She expects to stay close to her kids in retirement and she want to help them as much as she can,” says Gray.

Isabel has ample means to support her moderately affluent retirement spending budget of $68,000. However, there are lots of ways she could reduce spending if she had to by trimming areas of basic spending and cutting discretionary “extras.”

A tighter spending budget of $50,000 to $60,000 — which is closer to average — would still allow for a comfortable and fulfilling retirement, but it would require more careful prioritization of spending.

“In the extras alone, there is over $23,000,” says Gray. “That’ a lot of wiggle room. Could someone in her situation live on $50,000 or $60,000 if she had to? Quite easily.”

In addition to her full-time government job, Isabel earns a modest income on the side as a graphic artist. She expects to continue this part-time work in retirement, which should help her afford early retirement. She also helps care for an aging relative.

She owns and lives in a large, four-bedroom suburban home, a legacy of her former married life, which far exceeds her expected needs in retirement. She expects to downsize to a smaller house around the time she retires, thus adding to savings and reducing costs. (To be conservative, the retirement budget shown includes the high shelter costs of her current home.)

“She realizes one person in a big house is too much,” says Gray. “She’s ready to downsize when she needs to.”

Gray says that one goal of planning is to try to avoid getting forced into a financial corner and then having to choose between unpleasant choices under duress. It is better to build reasonable backup options into your plans and stay flexible.

In Isabel’s case, she likes her job and wouldn’t rule out working longer than five years. She has good prospects of earning part-time income well into retirement as a graphic artist. She can potentially bolster her finances by downsizing. Or she can trim discretionary expenses. If she ends up in better financial shape than she plans for, she can potentially travel more or give more money to her kids. “She’s got many options that are also positive options,” says Gray.

Renters

Isabel’s finances benefit from owning a large house with the mortgage fully paid off. It is often more challenging for retired renters of modest means to afford decent accommodation in high-rent cities like Toronto.

In Isabel’s case, her annual shelter costs of $17,900 are relatively high because she is paying a lot for property taxes, utilities, repairs and maintenance for a home that is far bigger than her needs. The average market rent for a one-bedroom Toronto apartment is $18,460 a year, based on the most recent annual Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation Rental Market Report published in January. That isn’t far out of line with what Isabel currently pays in shelter costs as a homeowner.

Thus many retired renters can afford to comfortably cover rental costs for a modest Toronto apartment if they have a budget of Isabel’s size (although finding a decent apartment at average rent levels is challenging if you don’t already live in one). Apartment rents become tougher to afford on a tighter annual budget of, say, $50,000. In that case, annual shelter costs of around $20,000 would take 40 per cent of the budget and leave $30,000 for everything else.

Taxes

The spending figures described so far exclude spending on income taxes. To give you a rough idea of a typical income tax bill, I have estimated typical taxes using the income tax calculator at taxtips.ca based on common assumptions for a senior (age 65 and older) in Ontario. (Note, in practice, actual tax amounts can vary widely depending on many individual factors.)

In this typical situation, for a single senior to generate after-tax income of $68,000 a year, they would need to generate gross income of about $85,700 and pay income taxes of roughly $17,700 (a 21 per cent average tax rate). To generate after-tax income of $50,000, they would need gross income of about $58,800 and would pay roughly $8,800 in taxes (a 15 per cent average tax rate). Seniors with higher incomes pay a higher tax rate because of the progressive nature of the income tax system.

Comments are closed.