Financial markets’ nastiest surprises often come when something that is taken for granted is suddenly called into question—whether it’s rising tulip-bulb prices, functioning banks or a lockdown-free existence. Investors had a tough time in 2022. But given how many trends changed direction over the course of the year, the real surprise is that it was not nastier. Here were the most important reversals.

End of cheap money

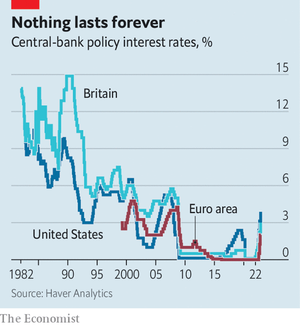

Future financial historians, looking back at the 2010s, will marvel that people really thought interest rates would stay near zero forever. Even in 2021, respectable investment houses were publishing articles with titles such as: “The Zero: Why interest rates will stay low”. Borrowing costs had been falling for decades; the combination of the global financial crisis of 2007-09 and the covid-19 pandemic seemed to have permanently glued them to the floor.

In 2022, persistent high inflation dissolved the glue. America’s Federal Reserve embarked on its swiftest tightening cycle since the 1980s, raising the target range for its benchmark interest rate by more than four percentage points, to 4.25-4.5%. Other central banks followed in its wake. Markets expect rates to stop climbing in 2023, with peaks of between 4.5% and 5% in Britain and America, and 3% and 3.5% in the euro zone. But the odds of them collapsing back to nothing are slim. The Fed’s governors, for instance, think its rate will finish 2023 above 5%, before settling down to around 2.5% in the longer run. The era of free money is over.

Death of the long bull market

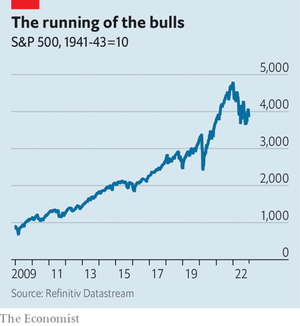

Bull markets don’t die of old age, goes the adage: they are murdered by central banks. And so it was in 2022, although the long bull run that ended had grown older than most. From the post-financial crisis depths of 2009 to its peak at the end of 2021, the S&P 500 index of leading American shares rose by 600%. Interruptions to the upwards march—such as the sudden drop at the outset of the pandemic—were dramatic but short-lived.

This year’s crash has proved lasting. The S&P 500 fell by a quarter to its lowest point this year, in mid-October, and remains down 20%. MSCI’s index of global shares has fallen by 20%. Nor are stocks the only asset class to have been bludgeoned. Share prices have fallen in part because interest rates have risen, raising the returns on bonds and making riskier assets less attractive by comparison. The same mechanism pushed down bond prices to align their yields with prevailing rates. Indices compiled by Bloomberg, a data provider, of global, American, European and emerging-market bonds have dropped by 16%, 12%, 18% and 15% respectively. Whether or not prices fall further, the “bull market in everything” has come to a close.

Evaporating capital

Capital was not just cheap in the last years of the bull market, it was seemingly everywhere. Central banks’ quantitative easing (QE) programmes, devised during the financial crisis to stabilise markets, went into overdrive during the pandemic. Together, the central banks of America, Britain, euro area and Japan pumped out more than $11trn of newly created money, using it to hoover up “safe” assets, such as government bonds, and depress their yields.

This pushed investors in search of returns into more speculative corners of the market. In turn, these assets boomed. In the decade to 2007, American firms issued $100bn of the riskiest high-yield (or “junk”) debt a year. In the 2010s they averaged $270bn. In 2021 they hit $486bn.

This year it has fallen by three-quarters. The Fed and the Bank of England have put their bond-buying programmes into reverse; the European Central Bank is preparing to do likewise. Liquidity is draining away, and not just from the risky end of the debt market. Initial-public offerings (ipos) smashed all records in 2021, raising $655bn globally. Now American ipos are set for their leanest year since 1990. The value of mergers and acquisitions has fallen, too, albeit less dramatically. Capital abundance has turned to capital scarcity.

Value beats growth

The bull run was a dispiriting time for “value” investors, who hunt for stocks that are cheap relative to their underlying earnings or assets. Low interest rates and qe-fuelled risk-taking put this cautious approach firmly out of fashion. Instead, “growth” stocks, promising explosive future profits at a high price compared with their (often non-existent) current earnings, stormed ahead. From March 2009 to the end of 2021, MSCI’s index of global growth stocks rocketed by a factor of 6.4, more than twice the increase of the equivalent value index.

This year, rising interest rates turned the tables. With rates at 1%, to have $100 in ten years’ time you must deposit $91 in a bank account today. With rates at 5%, you need only put away $61. The end of cheap money shortens investors’ horizons, forcing them to prefer immediate profits to those in the distant future. Growth stocks are out. Value is back in vogue.

Crypto implodes (again)

Those who think crypto is good for nothing but gambling and dubious activities could not hope for a better example than the fall of FTX. The crypto exchange was also supposedly the industry’s respectable face, run by Sam Bankman-Fried, a 30-year-old philanthropist and political donor. Yet in November the firm collapsed into bankruptcy with some $8bn of customer funds missing. American authorities now call it a “massive years-long fraud”. Mr Bankman-Fried has been arrested and faces criminal charges. If convicted, he could spend the rest of his life in jail.

FTX’s downfall marked the bursting of crypto’s most recent bubble. At its peak in 2021, the market value of all cryptocurrencies was almost $3trn, up from nearly $800bn at the start of the year. It has since fallen back to around $800bn. Like so much else, the affair’s roots lie in the era of cheap, abundant money and the anything-goes mentality it created.

Comments are closed.