According to the dictionary, the US went into a technical recession on Thursday, when it was confirmed that the economy had shrunk for two consecutive quarters.

The swirling controversy over how to define the term “recession” has even hit Wikipedia. After partisans engaged in a furious editing duel of the relevant pages, Wikipedia suspended most changes to the entry for “recession” as well as “business cycle.”

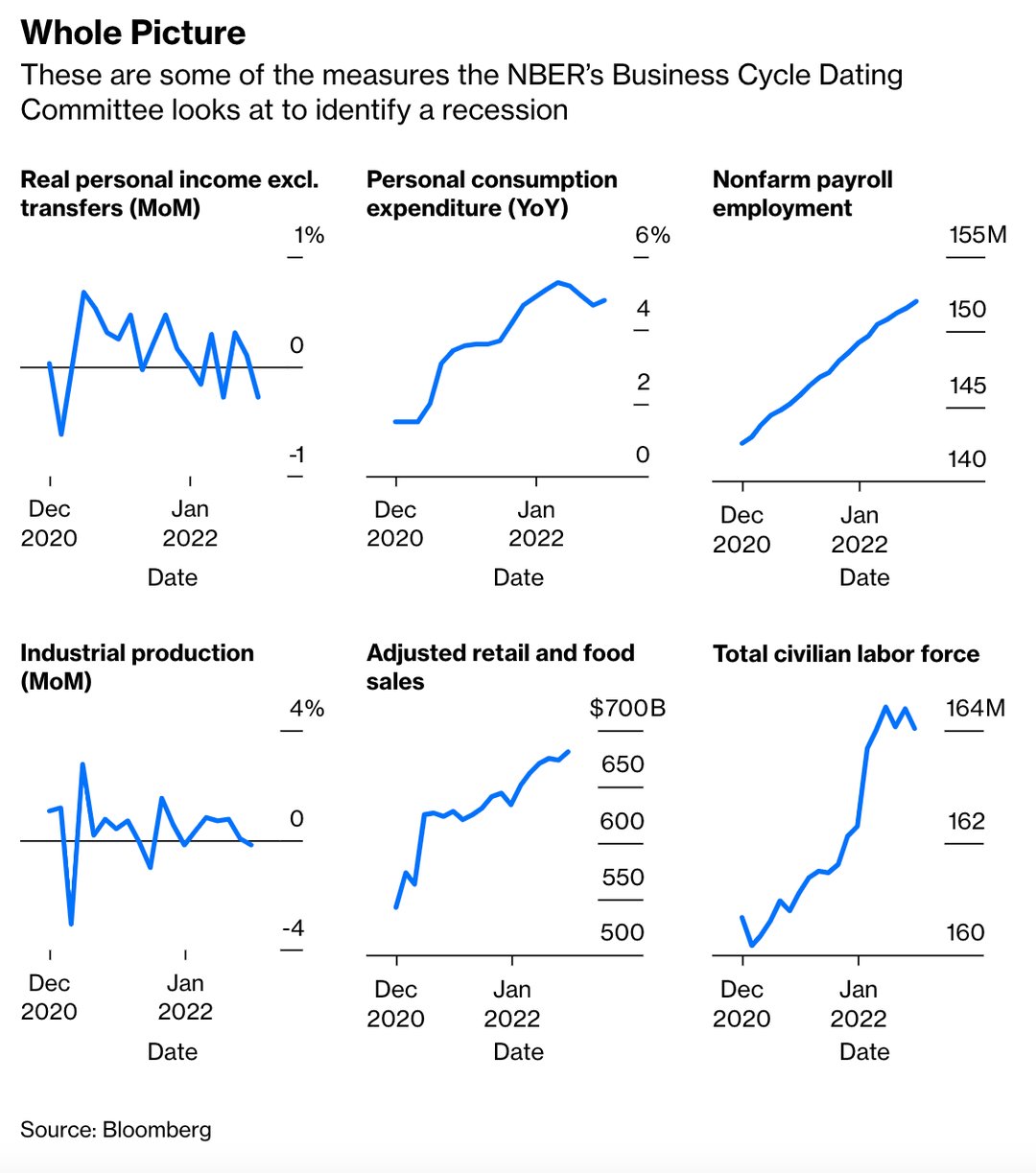

But that doesn’t mean this is actually a recession. The pleasure of announcing one of those goes to an obscure panel of eight economists who meet in secret and pore over several indicators to determine whether economic activity is, indeed, in a sustained period of substantial decline. Stephen Mihm writes that their work for the National Bureau of Economic Research is rigorous, but it’s always been as much art as science. There’s no equivalent to the laws of thermodynamics when it comes to recessions — they’ve come to us in a dizzying array of shapes and sizes, and no two have had the same causes or effects. A look at the indicators now gives us a little insight into the complexity of the task at hand:

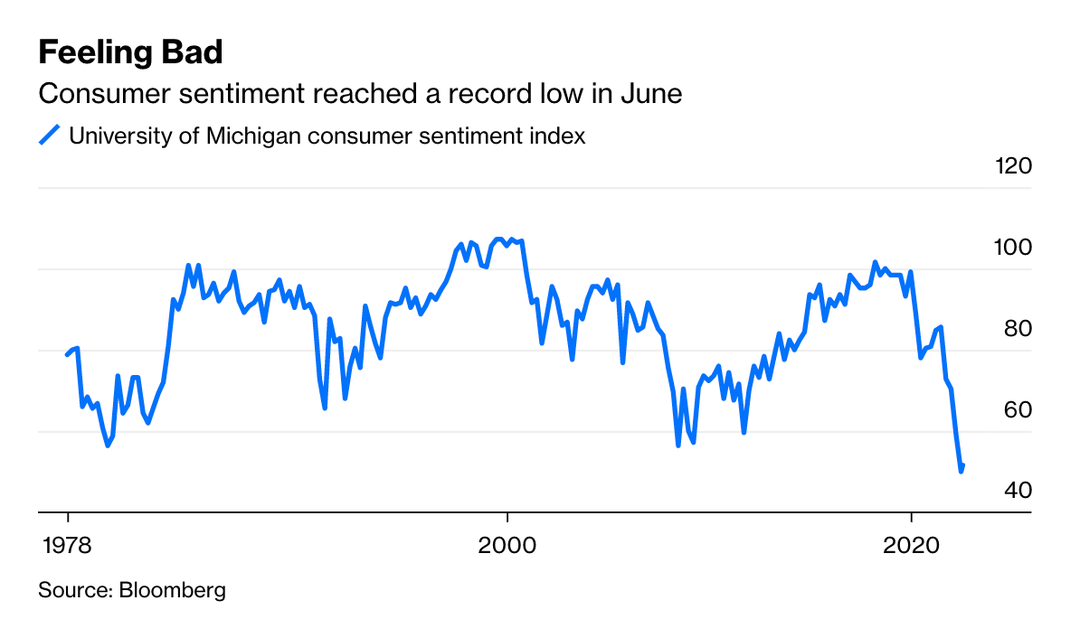

There are reasons to remain cheerful: Unemployment is still very low at 3.6%; household finances are looking healthy; and, as Paul J. Davies noted earlier this month, bank earnings have painted a picture of people going out and having a good time. But there are some bad vibes out there. Consumer sentiment is near a record low:

Could the American people manifest their own recession? Jared Dillian thinks so. For example, if people fear that the economy is about to go downhill, they’ll reduce spending, trade down to cheaper brands, postpone consumption and generally be more economical. If enough people do that, you get a recession.

There are now signs that consumers are getting into that defensive position. On Monday, Walmart ominously warned of lower profits for the second time in just two months. As Andrea Felsted writes, if the world’s biggest retailer is hurting, what hope does everyone else have? The problem isn’t that Walmart’s losing customers — it’s actually attracting them with low prices — but that consumers, as Jared warned, have begun spending only on what they need, buying cheaper brands and forgoing nonessential purchases. Walmart’s pain could easily spread to other consumer giants such as Nestle and Coca-Cola. Likewise, Brooke Sutherland notes that the pandemic boom in do-it-yourself home projects seems to be over, as demand for Stanley Black & Decker’s power tools dropped 16% in the second quarter. The company is now behaving as if it is heading into a recession.

But while Stanley is expecting a slump, the Federal Reserve isn’t. After raising interest rates again, Jerome Powell rejected speculation that the US economy is in recession, citing the “very strong labor market” as evidence. But the Fed should expect higher unemployment going forward, argues Clive Crook. Powell hopes that a softening of the labor market might reduce inflationary pressure without raising unemployment, but as Clive notes, it doesn’t always work out that way.

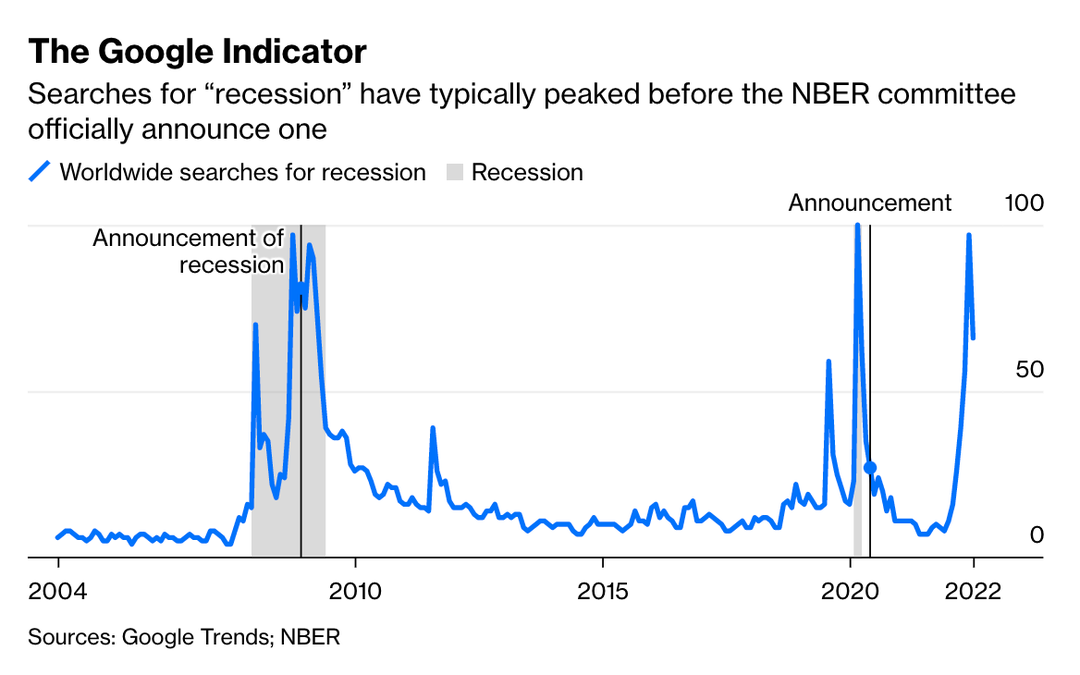

We’ll have to wait and see whether a true economic slowdown emerges. In the meantime, perhaps it’s time to propose a brand-new indicator: Google Trends.

NBER’s committee usually takes a while to determine the peaks and troughs of the US economy, but recent history shows search interest for “recession” lines up pretty well with recessionary periods. Keep your eyes peeled. An official announcement could be made in the coming months.

© 2022 Bloomberg L.P.

Comments are closed.