A stock market forecast can be a complicated, nuanced thing. Right now, though, any outlook boils down to a simple question: Are we on the verge of a recession or not?

If a recession lies ahead, corporate earnings are going to suffer. Stocks are about as tempting as three-day-old doughnuts.

On the other hand, if a recession is not in the offing, then broad swaths of the stock market could be rather appetizing.

iStock-1355813915

In my view – and, more importantly, in the view of most economic models – a recession is still the most likely possibility. The problem is figuring out when it might arrive.

For just over a year, the Bank of Canada and the U.S. Federal Reserve have been waging war on inflation. They have hiked interest rates at the fastest pace in four decades to discourage borrowing, nudge up unemployment and slow the economy.

Yet reality has shrugged off the hits. Despite the best efforts of central bankers to crank up the gloom, the North American economy keeps churning out happy numbers, especially on the jobs front. Remarkably, the jobless rates today in Canada and the United States are both lower than they were when the Bank of Canada and the Fed began their monster rate hikes in March, 2022.

This is not what experts predicted. Most economists – roughly three-quarters of those surveyed by the National Association for Business Economics this past October – had expected the U.S. to be in a recession, or close to one, by now. Similarly, Royal Bank of Canada economists had expected a recession to begin here as “early as the first quarter” of this year.

Does the fact we haven’t yet seen such a downturn mean that a recession has been averted? The optimists at Goldman Sachs think so. They point to fading inflation and a quick recovery from recent U.S. bank failures as reasons for optimism.

Other forecasters remain much more negative – and that’s understandable. You can find evidence for whatever tale you want to tell in the current muddle of data.

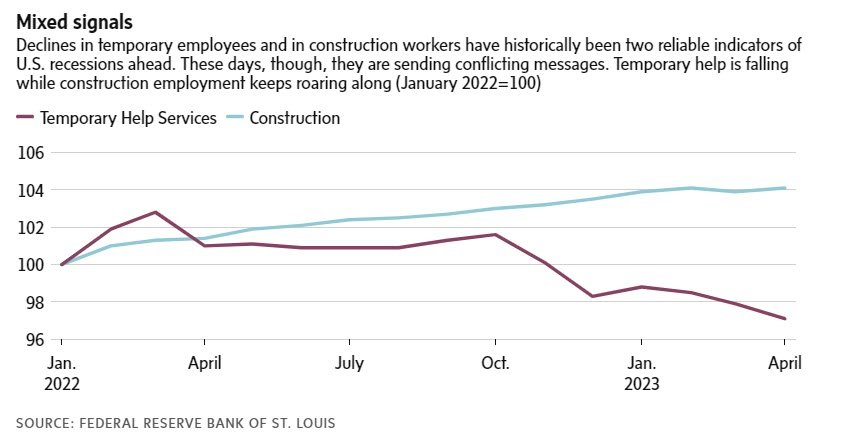

Look, for instance, at temporary employment and at construction employment. A fall in either number has historically signalled a U.S. recession ahead.

This makes perfect sense if you think about what lies behind the numbers. Companies typically lay off their temporary workers at the first whiff of any downturn. Similarly, property developers begin pink-slipping construction workers the moment rising interest rates start to bite into home building activity.

The problem for forecasters today is that these two venerable indicators are pointing in opposite directions.

Temporary employment has been sliding in line with the behaviour you would expect if a recession were looming. Construction employment, though, remains robust, just as you would expect if the economy were humming along.

To no one’s surprise, the stock market has been quick to focus on the positive story and ignore the negative one. As Lisa Shalett, chief investment officer at Morgan Stanley Wealth Management, wrote this week, Wall Street’s recent ebullience “has been premised on the belief that last week’s [Federal Reserve interest rate] hike was the last of the cycle, inflation has been tamed, a soft landing is assured” and key interest rates will tumble a couple of percentage points over the next year-and-a-half.

Ms. Shalett doesn’t buy this story. For starters, she doubts inflation has been whipped.

Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem appears to agree. He warned in a speech this month that, despite the progress made so far, getting inflation all the way back to the central bank’s 2-per-cent target “will take time and involve risks.” That does not sound like someone planning to slash rates fast.

The Fed may also prove to be tougher than markets expect. Harvard economist Jason Furman wrote this month that he thinks the Fed will have to hike its key federal funds rate one more time, to 5.5 per cent, before it can finally declare victory over inflation.

So where does this leave investors? A recession is still the overwhelming probability, according to economic models.

The Conference Board of Canada’s recession tracker shows a 94-per-cent risk of a downturn in Canada over the next 12 months. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s model puts the probability of a recession in the U.S. over the coming year at 68 per cent.

The catch is that such calculations still leave a wide period during which a recession might start. Interest rate hikes typically exert their effects over 18 months, so the vigorous increases of the past year are still working their way through the system.

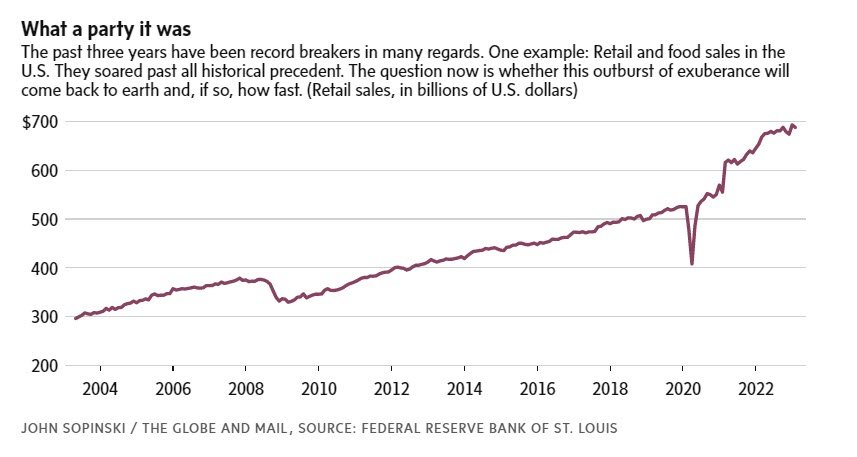

To complicate matters further, the current period is distinctly unusual. Look, for instance, at a chart of retail and food services sales in the U.S. over the past couple of decades. The past three years stand out. Sales during that period have surged to levels far above any previous trend.

Such unusual exuberance may require an unusually long time to come back to Earth. But chances are it will. Investors who have grown impatient waiting for a recession may just have to wait awhile longer.

Comments are closed.