Most of us know that physical fitness is good for our health. We need it to be the best version of ourselves in our work and our lives. For young professionals specifically, it’s been called the most important factor of success. It increases energy, productivity, cognitive acuity, mood management, collegiality, and more. But it also has the ability to make us feel really bad.

A new term, “exercise guilt,” has cropped up in the past few years to capture the disappointment we feel when our fitness goals go unmet. When we fall short, we get dispirited and are less likely to exercise at all, putting us at risk for a host of destructive physical and psychic effects, which compromise high performance.

Like any unmet goal we set for ourselves, it’s helpful to ask, is this guilt the result of falling short or shooting too long?

Certainly, we can exercise too little — and it appears that many people might be. Despite health clubs accounting for $37 billion annual revenue in the U.S. alone, exercise and physical activity have decreased. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cite the benefits, such as improvements in brain and mental health, disease deterrence and reduction, increasing musculoskeletal strength, and overall day-to-day functionality. Though we’re aware of these benefits, a 2019 RAND study found that of the approximately five hours of free time Americans have a day (time not taken by commuting, working, caretaking, and other basics), most of us choose to spend it not moving.

This was pre-Covid. Even with more time on our hands, research has demonstrated that, in the past two years, we’re moving less.

To find a healthy balance and rid ourselves of exercise guilt — yet another unneeded form of stress — we should consider whether we’re looking at the problem all wrong. We argue that, perhaps we’re failing to reach our goals, not because we’re lazy, but because for a variety of reasons (including the unhealthy body image pressures constantly thwarted onto us by the media) we push ourselves too hard, and set unrealistic expectations that inevitably lead to discouragement.

A part of the problem is that many people have failed to distinguish the difference between “movement” and that dreaded word “exercise.” For instance, in 2018, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published the Physical Activity Guidelines for adults. It says that “to attain the most health benefits, adults need at least 150 to 300 minutes of moderate-intense aerobic activity weekly [and] muscle-strengthening activity… at least two days each week.” Most of us read this and think: “I get it. I need to exercise more.”

But it’s not that simple. One-hundred and fifty versus 300 minutes of activity is a pretty broad range. Which is it? Can that total be met by doing more intense activity for a shorter amount of time or should it be prolonged? What’s the difference between moderate and intense aerobic activity? Does it vary across people? Is a short, slow, stroll worthless? What does muscle-strengthening activity mean? Lifting weights? If so, how often and how much? Will push-ups, pull-ups, and sit ups suffice? What about carrying that 20-pound baby around for an hour? Seems like lifting weights to us.

Clearly, the recommendation is not straightforward at all. We believe these recommendations would be more useful if they were framed in terms of movement.

When we, and many health professionals, say “movement,” we’re not just referring to intensive exercise. It’s an all-encompassing term that includes both fitness and the general physical activity we participate in day-to-day: walking from our desks to grab a drink of water, stretching before we go to bed, even getting up and moving around the kitchen to make breakfast. Exercise is planned and structured training, whereas movement is the natural by-product of expending energy during the course of everyday life. When we break the term down in this way, it becomes clear that most of us may be closer to our goals than we think. We don’t need to spend an hour on the Peloton five days a week to get in 300 minutes of exercise and be, by the science, “healthy.”

The American Heart Association now advocates for 10 minutes — yes, only 10 minutes — of movement a day. It can be as simple as taking the stairs two or three flights, walking to your colleague’s desk as opposed to calling him, or strolling around the block and saying hello to neighbors on the way, combined with what we used to call “warm-ups” (stretches and such, for just 30 seconds per day).

The transition into the post-pandemic world is a perfect time for young professionals — and anyone, really — to rethink their health habits and shed the “exercise guilt” they may be feeling. It’s time to recalibrate our routines to a moderate pace and place.

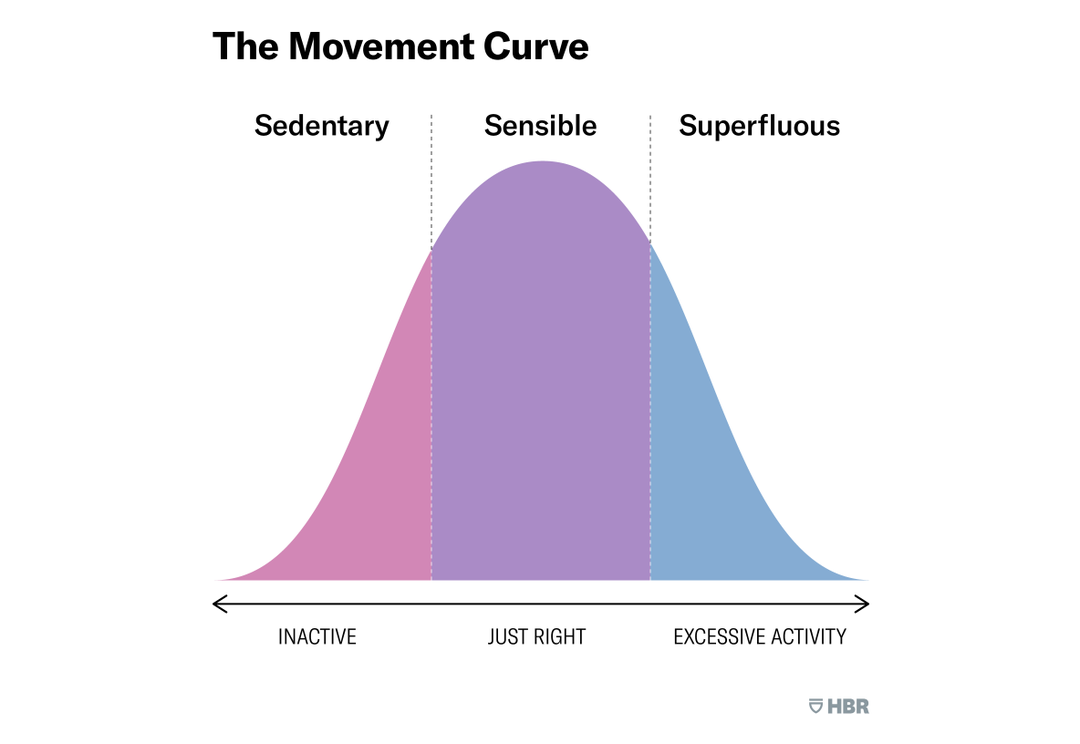

The Movement Curve below illustrates the relationship between health and exertion. It shows that too little or too much movement have equally harmful effects. That’s right — we no longer need to feel bad about not doing as much as our favorite fitness influencers. As always, for most of us, the answer lies in moderation.

Sedentary: This inactive lifestyle is categorized by too little movement due to excessive physical lethargy. Sedentary comes with health risks like obesity, type II diabetes, and heart disease. None of us want to reside here.

Sensible: The science says that this space is the best place, and it’s not that hard to get here. We don’t have to exercise obsessively to be healthy. Sometimes “sensible” is the best you should do.

Superfluous: As opposed to excessive lethargy, this is excessive activity. Too much exercise can lead to depression, injury, and compromised immunity. Always remember, perfect is the enemy of progress, and progress is what we’re striving for.

How much movement you need to execute to land in each category of the movement curve varies from person to person. It depends on factors such as sleep, height, weight, nutrition, metabolic rate, and genetics. (If you want the hard numbers, your physician is the best person to ask.) Our general advice is to optimize your time, productivity, and overall well-being. Don’t let anyone “exercise shame” you. (Yes, that’s a real thing.) Follow the movement curve that’s right for you.

Using the Movement Curve, we can realistically and modestly engage in daily routines to improve our bodily, mental, and emotional health. We can choose activities we enjoy without an all-or-nothing mindset. We can walk while chatting on the phone with friends and colleagues, we can drop and do 20 push-ups a few times a week, or play barbells with the groceries we’re unloading. The possibilities for movement are endless.

We can get to “sensible” without expensive gym memberships and unrealistic work-out programs, too. And we can avoid exercise guilt knowing that moderation is always the best remedy.

More than anyone else, young professionals should emerge from the pandemic with a new vision of health. That vision requires some discipline, sure. But it can be easily integrated into everyday life. Modern conveniences (thank you DoorDash and Amazon and Zoom), mean we don’t have to move to survive, but we’ve got to get our feet back on the ground to thrive.

We are made to move.

———

James R. Bailey is professor and Hochberg Fellow of Leadership at George Washington University. The author of five books and more than 50 academic papers, he is a frequent contributor to the Harvard Business Review, The Hill, Fortune, Forbes, and Fast Company and appears on many national television and radio programs.

Kelley Vargo is faculty in the Nutrition and Health Sciences department at the Milken Institute and School of Public Health. She is a behavior change subject matter expert at the American Council of Exercise.

c.2022 Harvard Business Review. Distributed by The New York Times Licensing Group.

Comments are closed.