AS COVID-19 infections fall and economies around the world begin to open, companies are facing difficult choices about their work culture. Should they demand that employees return to the office or allow them to keep working from home?

Workers seem to have discovered a taste for the latter. A poll conducted by Morning Consult in March found that 87% of Americans who were working remotely during the pandemic wanted to continue to do so at least one day a week after life returned to normal.

Among executives, though, the sentiment is more mixed. The boss of Goldman Sachs, a bank, has called remote working an “aberration” and expects staff based in America to be at their desks full-time by mid-June. Similarly, Google’s boss, Sundar Pichai, talked about the importance of “in-person” culture as he announced plans to phase out remote work by September. The company will, however, let staff work up to two days a week from home. By contrast, other tech firms, such as Facebook and Twitter, have said that they will allow remote working to continue indefinitely for those who want to.

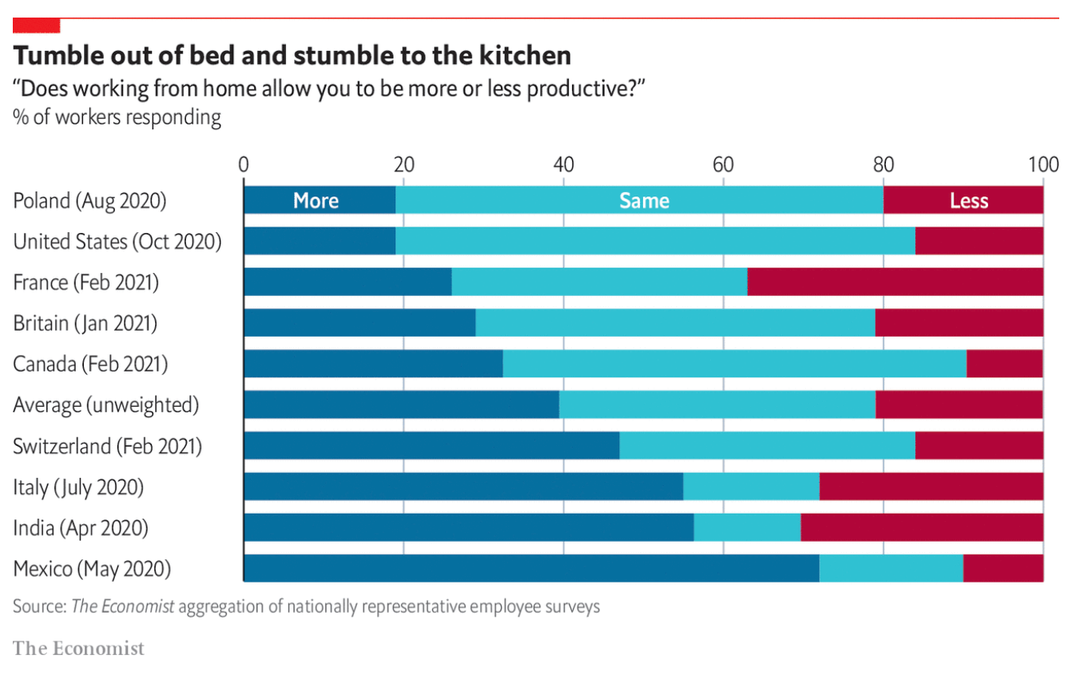

Whether remote working continues to be common will depend, in part, on the preference of employees and perhaps where they feel most productive. Covid-19 has provided an opportunity to take a deeper look at this question. Since the onset of the pandemic, pollsters and researchers have asked people whether they are more or less productive when working from home. The Economist has collected data from 12 of these nationally representative surveys from nine mostly rich-world countries over the past 12 months. We find that a majority of workers have consistently claimed that remote work either has no effect on, or even boosts, their productivity (see chart above). What is more, we find that sentiment has remained robust even as the pandemic has dragged on.

Such self-reporting needs to be interpreted with caution. Workers may be too optimistic about their productivity or praise remote work because they like working from home for other reasons. About half of the respondents to the Morning Consult survey in March said that they liked working from home because they could save time and money by not having to commute.

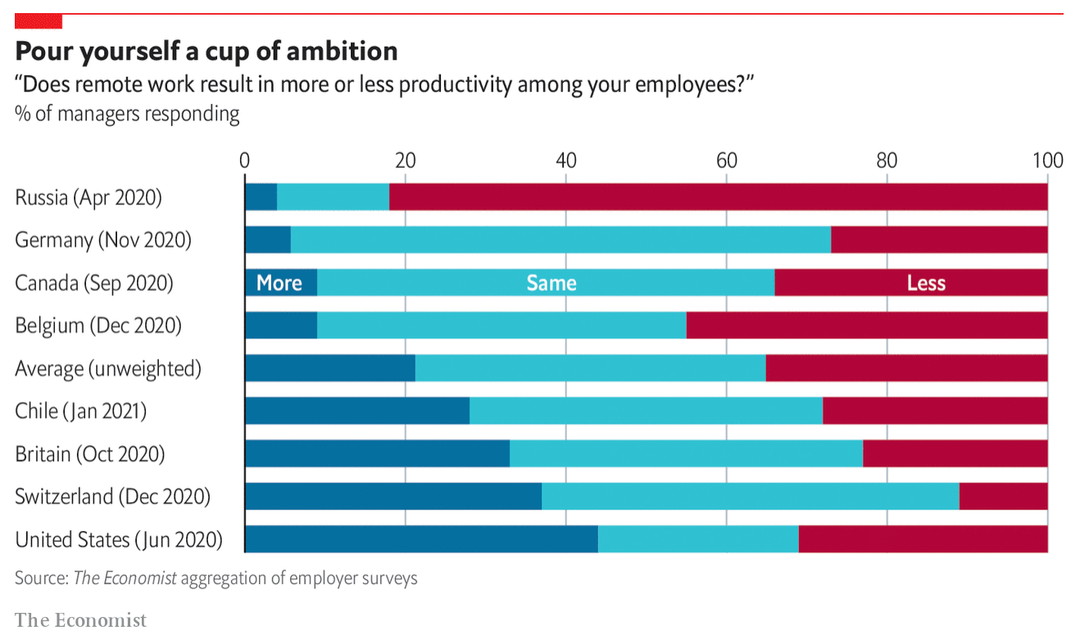

Surveys that have asked employers about their workers’ productivity (not necessarily at the same firms as those surveyed above) suggest that any productivity boost is not, at least, being noticed (see chart below). But bosses, too, may struggle to judge matters fairly.

To avoid such reporting bias, academics have tried to measure productivity more directly. A new paper from researchers at the universities of Chicago in America and Essex in Britain, led by Michael Gibbs, uses log data from an Asian IT company. The company’s tools track employees’ time spent working as well as the number of completed tasks relative to assigned ones. Comparing the performance of workers before and after the onset of the pandemic, the authors come to a pessimistic conclusion: once the company switched to remote working, working hours rose 30%, while output was static.

Other recent studies that use similar measurements offer less conclusive evidence. A recent paper by Harvard economists, which analyses tracking data from a call centre at a large American retailer, finds that remote working increased staff productivity. However, offering staff the option to work remotely risked attracting new unproductive workers to the company who were prone to shirking. Similarly, a team of Chinese researchers examined the amount of code written by 139 programmers at Baidu, a tech firm, before and during China’s lockdown last year. Differences in productivity emerged for some measures, but not on others. Output seemed to depend on the complexity of a project: working from home had negative effects on projects involving more than 20 people.

Plainly, more research is needed to determine how, and in what circumstances, working from home affects productivity. Thankfully, there will be lots of experiments to choose from, such as Google’s proposed two-days-a-week model. Any data-driven company worth its salt will no doubt be measuring the performance of those who stay at home and those who are in the office. In time, that will allow businesses and economists alike to understand what does and does not work.

Comments are closed.